Originally posted at Mixed Media Watch in Aug 2006

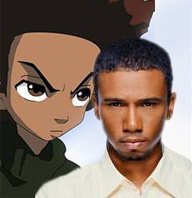

Separated At Birth?: Huey Freeman & Aaron McGruder

“I am one those red-blooded, flag-waving white Republicans you’ve heard about,” says one of Cartoon Network’s trademark teaser letters in its Adult Swim time slot. “I think The Boondocks is totally irresponsible viewing… and I love it!”

While Adult Swim likely aired those comments in their usual tongue-in-cheek manner, there is definitely an argument to be made for this show’s appeal to racists— not to suggest that “red-blooded, flag-waving white Republican” is in any way synonymous with “racist.”

Born of creator Aaron McGruder’s controversial 6-year-old comic strip, the animated show is one of this fall’s early successes on the network. Its ratings are proof of the marketing power implicit in the word “controversial”—a promotional buzzword often used in describing the original form’s handling of racial issues through the eyes of the 10-year-old protagonist, Huey Freeman.

The comic strip pulled no punches in its critical analyses of race matters, questioning George Bush’s legitimacy as president in one strip, and eviscerating questionable black leaders Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson in the next. Naturally, it was pulled from numerous publications with conservative readerships—a move which only boosted its credibility among core followers.

However, some readers have expressed disappointment in the televised version, which seems to have transitioned from unflinchingly honest satire to carefully veiled modern racism. The show creates a class of “good” blacks, often represented solely by young Huey—on track to become the most annoyingly self-righteous animated character since Lisa Simpson— and a bunch of “those people” blacks, led by his gangsta-wannabe brother, Riley.

But don’t take my word for it (at least, not just yet). Let’s take an analytical look at Episode 104, “Granddad’s Fight.”

The episode begins in an urban setting, where two young, black men in Hip-Hop-inspired clothing bump into each other as their paths cross. “Watch where ya walkin’, nigga,” yells the one in a red bandana, drawing a gun.

From this point, series creator McGruder seeks to conclusively explain the origins of a particular brand of violence in contemporary American society. He does so by conducting a series of informal experiments, the first of which is, at this point, already underway

Main Experiment: 2 Black Subjects

“Watch closely,” instructs Huey, our narrator. “You are about to experience A NIGGA MOMENT,” with the words appearing onscreen for added effect. In the next frame, the savvy viewer is reminded exactly why cartoons have always been extremely effective racist tools since the pre-minstrelsy era: the medium’s creator can contort physical attributes of cartoon characters in ways that would be far more difficult—and less effective—with flesh-and-blood actors.

Here, the bandana-sporting figure and his wifebeater-wearing adversary (we’ll call them “Red” and “Beater”) are shown as modern, Anime-style updates of classic brute stereotypes. As they unload bullet rounds into one another, their bodies assume exaggerated “gangsta” stances. Their large lips frame feral, gritted teeth, and their nostrils flare down at the viewer in creatively menacing low-angle shots. Large white orbs blaze where eyes should be—their tiny, pinprick pupils exposing them as the “talking beasts” Buckner H. Payne warned of in his postbellum publication, “THE NEGRO: What is His Ethnological Status?”

As if to explain the rampant, cartoonish use of a word the viewer will have to endure for the duration of the episode, Huey goes on to define the “nigga moment” (according to Webster’s) as “a moment when ignorance overshadows the mind of an otherwise logical black male, causing him to act in an illogical, self-destructive manner… like a nigga.”

This rhetoric is often used by modern racists, who defend their use of the word “nigger” by distinguishing him from the “black man.” This theory suggests that a black man is a goal-oriented, responsible individual (a “good one”), while a nigger is a dangerous ne’er-do-well who deserves to be regarded as the subhuman scourge of society. Thus, by only using the term “nigga” in describing these figures, McGruder creates a trap door through which he can evade any accusations of racist generalization.

As shown in the previous encounter, nigga moments seldom end well. Huey buttresses this point by going on to list the top killers of black men in America:

- F.E.M.A.: Here, the old Boondocks analytical wit resurfaces briefly, obviously referencing the government agency’s shoddy handling of the Hurricane Katrina evacuations.

- Pork Chops: McGruder blends the comic strip’s reproachful, “tough love” critique of black issues with the new trend of subtle mockery present in the animated series. While poor dietary choices have become a legitimate concern among blacks in recent years, this reference hints at the mythical black obsession with greasy, unhealthy food often used as a punchline by black comedians.

- Nigga Moments: While it is an undeniable fact that black-on-black violence is one of the leading killers of black men, the term “nigga moment” suggests that such belligerence is an exclusively black trait.

But is McGruder really trying to say that blacks are the only ones capable of such misplaced aggression? He doesn’t let the viewer ponder this for too long before introducing a control experiment involving a white pedestrian.

Control Experiment 1: 1 Black, 1 White

When challenged in a similar manner by Beater, the white character begins to respond, but thinks better of it:

“Wait a minute. I’m white!”

And with that, he walks away, laughing as Beater yells in the distance. Beater is hurt by the white man’s unwillingness to stoop to violence—the only conflict-resolution system accessible to him. Thus, he insists the confrontation continue, for it is “a perfectly good moment to throw your life away.”

Here, McGruder brushes aside any suggestion that a white man could be entangled in these “nigga moments.” I’m certain that Glenn Moore, the 20-year-old black man whose skull was fractured by a group of white Howard Beach, NY, residents last summer, would disagree. But Huey goes further to reveal that whites avoid confrontations with blacks in recognition of their own superiority, and never due to a fear of the menacing blacks portrayed (albeit accurately, in Beater’s case) by the media.

Control Experiment 2: Whites in Their Own Habitat

Huey goes on to debunk the foolish myth that one can escape nigga moments by simply moving away from them, explaining that “niggas always have a new trick around the corner.” Even with the white subjects now safely sequestered among their own kind, they are still in danger, for into every white life a nigga must fall.

And in today’s episode, his name is Colonel H. Stinkmeaner. He is first seen driving recklessly through an idyllic sub-urb (a scaled-down, suburban recreation of an urban metropolis), causing pandemonium as only a blind driver in a residential area can.

Conclusion:

“Every nigga moment begins with the nigga,” says Huey. “Without that key element, all you’re left with is peace and quiet.”

Stinkmeaner, as his name suggests, is a completely flat character defined only by “his love of hate.” A blind geriatric, he uses his disability as leverage with which to antagonize a world that dares not fight back (as evidenced by his stubborn insistence on driving despite total vision impairment). It would seem he is being used as a symbolic representation of African-Americans, who, as some conservatives believe, use their minority status in a similar manner (i.e.; playing “the race card”).

Having terrorized his quota of whites for the day, his focus turns to Huey’s grandfather, whose car he repeatedly and deliberately rear-ends for parking in “his” disabled parking space. By this time, it is clear that Stinkmeaner is a target the audience is welcomed to loathe at first glance. His flint-gray hair and eyebrows sprout wildly from his bald head, his thick lips mangled in a sour, toothless grimace as he spews copious doses of insults and saliva. As he berates Granddad for parking in his space, his every statement is punctuated with the word, “nigga.” But in order to differentiate this from our hero’s own frequent use of the word, his inflections are given a more distasteful, “ghetto” flavor—pronouncing the word as “niukka.”

Granddad’s day is definitely taking a turn for the worse after a very auspicious start; earlier, he was so overjoyed at his purchase of a new pair of Nikes that he regaled his grandsons with the “New Shoe Song” and its accompanying dance.

Unfortunately, Stinkmeaner’s nose—thanks to a heightened sense of smell (or possibly his distinct “niggaism”)—is able to detect Granddad’s new pair of shoes, and proceeds to stomp on them. If mainstream media have taught you nothing else, they have definitely warned you never to mess with a black man’s shoes. According to Huey’s narration, these “hundred-and-fifty-dollar landmines” are catalysts in six out of every ten nigga moments, and it’s no surprise that Granddad loses his cool and engages Stinkmeaner in a fight. He loses.

As Granddad goes about scheduling a rematch, Riley is left home watching a Hip-Hop award show, where Eat Dirt—a wild-eyed rapper—is honored with the Artist of the Year award. He is the very image of drug addiction. His rotting teeth hang tenuously from diseased gums, his unkempt afro is replete with random debris, and his clothes cover very little of his haggard, tattooed physique. As he approaches the stage to accept his award, he is blindsided by a chair and the entire auditorium erupts in a bloody melee.

This is scene is so venomous in its depiction of Hip-Hop culture that it is hard to imagine a white-supremacist satirist doing more damage, and one has to wonder what McGruder’s exact intentions are with this episode.

Overcoming his initial disappointment at Granddad’s insistence on a rematch, Huey assumes the role of his Sensei, training him for the big fight. If Huey’s superiority over the other black characters isn’t already clear, McGruder devotes the rest of the episode to making that point obvious. As Granddad defers to Huey, taking his every word as gospel, Riley begins promoting the fight—“The Slapfest in Woodcrest”—around the community. Ever the black hustler, he sells tickets, takes advance orders for the DVD release, and naturally secures for himself “a little action on the side.”

To further elevate Huey, Uncle Ruckus, a self-hating black menial worker is introduced. Among his many disparaging comments about blacks, he comments that they “don’t possess the strength of character or mental quickness to be a great fighter.” In a humorous reversal of the iconic dialogue from Eddie Murphy’s “Coming To America,” he goes on to list a host of great white fighters, preemptively dismissing any argument for black fighters that involves “pull(ing) Muhammad Ali out ya’ ass.”

Uncle Ruckus... Some Relation?: Similarities deeper than the physical.

As the audience is invited to laugh at Ruckus’ character, many will probably miss the parallels between his and McGruder’s voices. Having spent a lifetime in the service of whites, Ruckus has come to hate his people and curse his blackness (which he refers to as his “ailment”). In hopes of one day gaining acceptance from whites, he devotes much of his time to exaggerating real and imagined follies plaguing the black community, often to great comical effect. McGruder (or at least, the psyche of McGruder that is reflected in this episode) is cut from the same cloth.

As a black entertainer, McGruder seems to be taking the Cosby route—looking to elevate a white populace’s estimation of him by enumerating the many ways in which he is superior to a “those other blacks.” Creating in Huey a condescending superego of the black community (with whom he shares an uncanny physical resemblance), McGruder makes the same mistake as many blacks in America today. In their attempts to prove their worth to their white contemporaries, they establish themselves as an “exception to the rule,” rather than provoke the mainstream to revise the rule or abandon it altogether.

If successful in parlaying this SuperNegro stance into commercial success, the performer only further widens the gulf between the “good ones” and the “others”—thus strengthening and validating modern racism.

While promoting the first season of his animated show, McGruder has had to walk a thin line: telling white conservatives much of what they want to hear, while maintaining the “angry, political black male” persona that has gotten him this far. In the interviews leading up to the show’s premiere, McGruder was known to reel off a long list of blacks, he felt, had let down the race.

While critique of that nature may be valid, it is interesting to note that he seems to have abandoned the other elements that defined the comic strip. Gone is the Huey that called an anonymous FBI tipline to alert them of Americans backing terrorist cells—including on his list Ronald Reagan and the CIA. Such government criticisms are long gone, and there is nary a mention of racism in America.

When discussing the pressure he faced to axe a segment featuring the abduction of Oprah Winfrey by a gang of thugs, he somehow manages to place the blame on her. Tapping into an existing sentiment that Winfrey may have become too powerful, he ominously states that “I think we should all have a healthy fear of Oprah Winfrey.”

Promotion tactics like these are becoming de rigueur for black entertainers trying to appeal to the largest possible audience. Rapper, 50 Cent recently publicly absolved government agencies of the mass carnage that arose in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, stating that race had nothing to do with it, and it was merely “an act of God.”

But by avoiding racial issues or restricting all criticism to the black community, artists like McGruder often become tools of modern racists, who are able to attack a racial group without getting their hands dirty. Comments from such entertainers give extra weight to modern racist rhetoric by proving that “even their own people” hold these beliefs.

However, in true Modern-America style, few are ready to fight that battle. To many, this new McGruder is either a great satirist or an illustration of the degradation of Black America. However, neither party is willing to use the incendiary R-word on a black man, adopting the simplistic logic that “if a black man says it, it has to be OK.” An example would be humorist Zepp Jamieson.

“Is Boondocks racist against blacks?” he asks on his website. “Go look at a picture of Aaron McGruder. Get back to me.”

[…] and Stone really showed their asses this time, though. Much like Aaron McGruder did with The Boondocks, they’ve come to reveal themselves through the words and deeds of one of their […]

As a black male, I have often viewed the TV version of the Boondocks as a racist show, mainly because it glorifies the ignorance of black culture on a white network and for mostly white viewers. Its nothing more than a more vicious blacksploitation of my race and I feel that Aaron McGruder is a racist and an Uncle Tom.

You’re crazy. Aaron McGruder is NO Uncle Tom. You simply have no understanding of satire. Do you think The Boondocks is more harmful than the crap that’s played on BET? There you constantly you women being degraded and young black men glorifying living lives filled with vice. McGruder shows how stupid that mentally is in The Boondocks. SATIRE research it learn what it means then watch McGruder’s show. Peace

I responded to the comments left and not to the actual post. However, I must say that I completely disagree with the writer. You’re not seeing the satire in McGruders work. Are you telling me that there hoods, “ghetto,” aren’t filled with ignorant mislead young minorities? I know that statement is harsh, but it is true. The reason for it is even harsher. It’s because they lack education. Minorities don’t get anywhere as many opportunities as majorities, white ppl. This starts from schooling all the way up to careers. Sometimes the best way to help ppl is to give them a reality check. That’s what McGruder does. You know how many parties I’ve been to that ended because someone got stabbed for stepping on someones shoes? Too many to count and that’s ridiculous. The writer doesn’t seem to fully understand McGruders work. You should look into more artist like this. Lupe Fiasco has a track called the The Cool. It basically says if your selling drugs trying to be cool don’t be surprised when you go to jail. Is that racist? How about this in another track he says lets be cool get the big titted girls and cocaine. How’s that? Read up on satire..then you may be able to criticize true intellectuals.

Hi Chris,

Thanks for your comments. Very thoughtful stuff.

I’m very familiar with both satire and the Lupe album, The Cool.

McGruder’s is neither.

But I appreciate your impassioned explanation of your point,

If I’m not mistaken (I may be), the reference to Pork Chops being a leading cause of death with African Americans, was in regards to a child who killed his brother over a pork chop in Chicago. It is a more direct and applicable approach then just “poor dietary choices”.

Also, I do see that you have good point in your article but I would still have to disagree. I think that the comedy in The Boondocks come from the hyperboles it uses. Even though they are sometimes exaggerated, there are many African American who can watch the show and laugh at a scene and say “I can relate to that”. The problem with the Caucasian audience is the fact that most can’t. The goal of this show, I’m my opinion is to shed light on situation while suggestion that I should not be take too literally or to lightly. That is not an easy thing to do, but I think it has been accomplished, per se.

Perhaps that’s the problem. Is this show created as a shared inside joke with blacks, or an invitation to mockery for whites? My issue with McGruder arose when I began to suspect it was the latter.

Thanks for commenting.

i was the only black guy amongst my FORMER friends

and they loved teh boondocks

i hated the show and havnet watched a singe episode

i dont want black people to be portrayed this way

this is not how my family behaves

this has nothing to do with how my relatives are

or the black people i know

all black people i interact with are dsecent and intelectual human beuings

not this halfanimals mcgruder depicts us to be

it puts me down to watch this show

we had enough of depictions of blacks that take of them their dignity

thats why ist a comic because with real black actors they couldnt do this racist bullshit

i think he is one of the black people who believ what the racists say

adn he blames the blacks for him being discriminated against

so in his brainwashed mind he turns against the fellow victims of opresson not the racist opressors

people like macgrudge

are just plain weak

they are the type who blame the rape vcictim instead of teh rapist

its the racists who are responsible for the bad image black people have

its the racisats who are responsible for black peoples suffering

and i believe only people who arent racists can see it

everyoen sins but racists see it only when a black person does it

we need to fight racism anitsemitism and sexism

i am tired of this uncles toms….

you’re not even making any sense, you’re stereotyping all black people to say they’re all upstanding intellectual decent human beings, which may be true for a lot of families but not all, and that goes for every race, go live in south central for a month and see how you change your mind, McGruder shows all variety of black people

I’ve also noticed the show is a invitation to mockery, or should I say (Black Jokes for White conservatives). Similar thing happened to hip-hop, eighty percent of the purchasers are white suburban teens, and all we hear is sell dope and the word nigga on the radio. I figured out why this tight of rap got commercialization and DJ support, because white teens can hide behind the lyrics of hate, made for the ones buying it. McGruder’s show targets a white audience with the intent of reiterating racial beliefs. As stated in the post, the show does restrict criticism to the black community only. I reflected on the “Nigga Moment” episode and came to the same conclusion, that this “niggaism” was a subhuman part of the black man’s psyche, a disease, as uncle Ruckus suggest. To suggest that is the work of eugenicist, social engineering at it’s worst. I have added this link and subject under my boycott Sony campaign on facebook, the link is below. Only way to stop blacksploitation is bring to light!

http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=136295566397320

There are a lot of negatives directed at white culture in the show; but you have to be able to make the connections. The reason why it isn’t always blatant is because he still has to operate within the framework of the white system just like everyone else in order to keep the show going.

For example, Gin Rummy and Ed Wuncler the III are both upper class white guys who are constantly engaged in criminal activity and get away with it every show b/c Ed Wuncler the I is a rich white guy and well respected in the community; which, along with their ability to co-opt gangsta rap stereotypes, is a representation of the power of white privilege.

As far as Uncle Ruckus goes; yes clearly he “hates” black people, but he is representing the self hatred experienced by many blacks as a result of conditioning within white society…if you really look past what he is saying about black people, the ridiculous over the top glorification of white culture and white heros is actually an indictment of how we have all (black, white, Mexican, whoever) been conditioned to believe these things about what it is to be an American white man; that it is “God’s gift” to be born white, and that the only important contributions to society have always been made by white men. Uncle Ruckus’ character is not meant to be glorified, but reviled.

For anyone paying attention, the show actually seems to me to be a portrayal of how white society has made these different black characters lose their minds or manifest completely destructive behavior…or in the case of Huey, first a revolutionary mindset which later transforms to almost a disgusted apathy. Humor is used to make it more palatable and to keep it entertaining to the viewer, but what you have here is a daring social critique. You have to be willing to transcend the surface level of what “nigga moments” appears to be and what it actually reveals, which is a socially constructed imperative among some American blacks to destroy themselves and each other over trivial things. Again this is more of an indictment of America, but still demands black self accountability.

i believe a show like this need balance, there is a difference between using satire and degrading almost every black character in the series. a bit is shown about the ruthlessness of rich white people and even the ‘wiggers’ but they almost always finish the show somewhat dignified. that cant be said of the black people in the show. most of what is shown are stereotypes already known to half the world, there no need reliterating it if he isnt going to balance it out with something positive.You talk about deeper nmeaning in quotes like “For anyone paying attention, the show actually seems to me to be a portrayal of how white society has made these different black characters lose their minds or manifest completely destructive behavior…or in the case of Huey, first a revolutionary mindset which later transforms to almost a disgusted apathy.”

that might be as well true but with stuff like that hidden within the show and a more destructive protrayal of african americans put out there, which part is more likely to be absorbed/noticed by the viewers. like i said earlier this show will do a lot more harm that good if left in the state it is in.

even an opposing charcter to uncle ruckus will help give viewers a broader look at african american lives.

im just gonna big this show up because i honestly agree with chris because all the boondocks is trying to do is put out the truth about whats going on and how blackpeople are doing nothing about their own race. and i honestly believe that huey puts out the real stuff. “dumb niggas love gangstalicious the same way fat women love oprah”. i think this is the truth but the oprah part was to add comedy to the show.

In the interest of full disclosure, I will same I am white. I grew up in an upper middle class neighborhood in a small, Southern town but I went to public school with everyone else.

With that out of the way, I do think the line The Boondocks walks is a very, very delicate one. I’m not at all surprised to hear cries of blaxploitation or outright racism–and due to weaknesses in the shows presentation, there are elements of both. At the same time, I do not believe this is the overall tone or message of the work.

The cry of racism becomes problematic when there are the same criticisms in the show leveled against whites, and even the efforts of black people to “be” white (case in point: Tom Dubois, an obvious “Uncle Tom” type character). But Huey, as self-righteous as he can be at times, embodies uniquely black and positive traits: an understanding of race relations in America, weaknesses in black and white people’s behavior, and a strong sense of his own racial identity.

The show is hyperbolic and has modern black struggles as the foundations of most episodes’ plots. It is never suggested in the show these apply to all black culture, just the problematic sectors. Thugnificent and Gangstalicious, for instance, are perfect illustrations of white corporate influence co-opting and robbing blacks of a truly intelligent culture in pop music. Huey’s contempt for them is justified, as popular, modern black rappers tend to rap about partying, how awesome they are, hedonism, and almost militant anti-intellectualism. Riley’s love for these public figures is not a mockery of uneducated, highly impressionable black youths, but a warning to black viwers to NOT endorse these kinds of role models, lest they end up like Riley.

Also, anyone who takes Uncle Ruckus seriously may want to adjust the tone with which they watch the show. While some of his observations are reinforced by moments in the show, the episode “The Uncle Ruckus Show” shows him to be a cowardly, completely delusional, culled individual impressing negative feelings about himself onto others. Much like Riley’s relationship with Lethal Interjection, it’s a positive example of what not to be.

This is a point that’s completely personal, but I also get the feeling watching–as much as I love it–that the show is not “for” me. A lot of its points just don’t apply to me, and I feel if it was a show about dumb black people for racist white people, I should be saying: “Ha ha, yeah! That IS right!” But a lot of times I come away entertained, but merely as an observer.

I could say more, but that’s all I feel like typing. Hope this adds something to this discussion.

As a white initially unfamiliar with the black community in any detail, I couldn’t help noticing that if the animation had been directed by a white rather than a black, there would be strong accusations of racism so it would amaze me if aaron and the uncle tom label were not somehow used in the same sentence occasionally. Indeed, that is how I found your article but usually he is praised rather than critiqued. Aaron has stated that most of the topics aired are in response to fan requests based on real life occurrences so his vision that it is high time blacks stopped hiding behind a sense of learned helplessness and the entitlements of victim hood and made serious efforts to address social problems seems to be shared by some fans.

Now I have 5 years experience within two black communities (Richmond and Oakland, CA) that take turns vying for homicide capitol of the US due to dating black women. I have been invited to numerous black events where I observed first hand the behaviors mcgruder calls out so clearly, or I heard other blacks disparage those that behave this way while taking pains to remind the only white in the room that only blacks are allowed to critique other blacks. My future brother-in-law majored in black studies at amherst so he feels quite confident and condescending as he categorically blames all black social problems on whites while quoting from only black academics. Your rant reminded me of him but I fully enjoyed the revamp of the episode dialogue because each scene cited triggered a replay of at least two similar events in my head causing laughter at the insanity of it all. The stories I could recite … Anyway, the episode was hilarious.

I would point out that the two gangsta characters that Riley was cheering on, Eat Dirt and Gangstalicious are meant to be comic on several levels while also referring to real life sources. The homophobia while being gay. The inability to use a gun properly while bragging about gun ownership and the power it provides. The supposed wealth portrayed in videos when everything is actually rented. The media claims that the beef had now escalated to catastrophic warfare over the use of a chair as a club in order to boost ratings. The entourage of Eat Dirt’s inability to articulate any coherent thought at all. The constant hand gestures with no real meaning attached. The casual use of the N-word by people supposedly offended by it.

If you find these characters objectionable, then clearly you aren’t getting out enough and need to mix it with more thugs that may, like lethal injection, congratulate you for reading. They do exist as I’m met more than my share. Usually, I have a book or magazine in hand and their eyes glaze over when I answer the question, “what am I reading?”

If you find these characters stereotypical, then I respectfully ask you to watch an episode again with an imagined pair of white eyeglasses and then get equally offended at the portrayal of whites. we aren’t all rich, foolish and lazy nor do we all go crazy when a black rapper strolls into town. sometimes, I think aaron hasn’t actually met any whites yet but then I remember that he is trying to be funny. True story: the earlier episode where granddad offers wuncler some cheese actually happened to me at an exhibition of the history of black women hairstyles. It was funny and ironic. I briefly wondered why Tom can be seen dating a white while the reverse cannot be true but then I experienced first hand the black racism against mixed couples and shared the stress my girlfriend experiences for “acting white” or “selling out”. As Cali has so many immigrants and a healthy mix of races, I do find the emphasis on juxtaposing whites with blacks a bit myopic but any conversation with my girlfriends’ parents, still pretending life has not changed since 1963, and suddenly everything makes sense. I’m actually surprised that they allow us to date at all. I applaud aaron for emulating mark twain in his word-for-word recording of life in his times. However, like dave chapelle, i often wonder how he measures success given that not everybody is able to appreciate the humor or suggestion that the black community can do better and probably should. I think the lectures that worked well for past generations just don’t carry the same weight today and it may be time for a new generation of critics.

American history, any color, is a collection of experiences that differ between groups because of social or economic status or personal choice but overall are shared when viewed between generations because of our willingness to accept change and new that inevitably puts a shelf life on anything we do and makes just the act of living dramatically different when comparing grandparents to grandchildren. If you consider what products and services are marketed to the black community and how it is advertised, at least businesses have agreed that multiple social classes with differing levels of disposable income now exist. If you consider the fairly recent in time protest against the quality of shows on BET or the debates about the value of Tyler Perry’s performance art, you can make the same argument that multiple levels of entertainment viewers now exist. Why then do you continue to perpetuate the pretense of a single monolithic black community? Why can’t it be fragmented as others are? If it can, then surely there is room for aaron’s art in at least one of those segments.

black people are sooo funny. love to keep your heads in the ground. google crime stats. a rose is a rose. per capita you are the most violent low IQ race. stats dont lie.

“Stats don’t lie” should be in the running for the silliest words ever uttered.